Erich Von Stroheim’s

Greed Location Survives In San Francisco

The stately Victorian at  1923, it was the focus of intense media

attention, a magnet for scores of magazine reporters. Today, it is

distinguished by being the only major surviving set from Greed, the most

brilliant, innovative, and controversial

1923, it was the focus of intense media

attention, a magnet for scores of magazine reporters. Today, it is

distinguished by being the only major surviving set from Greed, the most

brilliant, innovative, and controversial

Erich Von Stroheim was the

film’s director, a man who was best known as “the man you love to hate” for his

numerous screen portrayals of Teutonic villains.

The central

character is a self-taught dentist named McTeague

(Gibson Gowland). When his wife Trina (Zasu Pitts) wins $5,000 in a lottery, their life begins to

unravel.

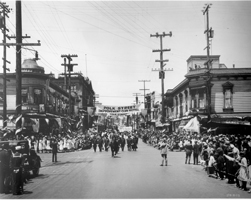

Von Stroheim insisted that the movie be shot on location using

real buildings, not the standard breakaway sets. The main set was the Victorian

at 601 Laguna, which the director found perfect for his needs. A second floor

room that overlooked Laguna and Hayes was transformed into McTeague’s

Dental Parlor, complete with garish gold tooth sign. The movie was set in the

decades before World War I, so the Victorian was festooned with beer and wine

ads. Since this was the height of Prohibition, special permission had to be

granted for such ads, however bogus, to be publicly displayed.

Realism became an obsession for the director. Hidden

cameras often included “real” people in many scenes. In one celebrated

incident, Zasu Pitts as Trina discovers a murder in

an alley near the Victorian. While Von Stroheim’s

hidden camera rolled, Pitts ran out into Laguna in character, frantically

flagging down passersby for help. A real crowd gathered, the police were

summoned, and a reporter phoned in the “homicide” to his editor. In another

incident, a car was reported for almost “running down” a man as he boarded a

streetcar. The man was an actor, the vehicle Von Stroheim’s

camera car.

Stroheim’s

camera car.

Von Stroheim ended up with a

film that was somewhere between 42 to 45 reels in length—about 9 hours long. Greed

was started as a Goldwyn Studios picture, but by the time it was finished

Goldwyn had merged with a new entity, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Studio chief Louis B Mayer hated the picture, and

eventually it was cut to what was termed a more suitable “commercial

length”—some 10 reels. It was this fragmentary version that was released in

December, 1924

An appalled and distraught Von Stroheim

disowned his mutilated “offspring,” calling it the “skeleton of my dead child.”

By most reports the edited footage was destroyed, melted down for its silver

content.

Greed became celebrated as a kind of lost American epic, one of the greatest films ever produced. In 1999 a ‘restored” version of the movie was aired by Turner Classic Movies. This 239 minute version—99 minutes longer than the original 1924 release—was fleshed out with a extensive montage of stills.